WilsonNCTeaParty

Writing

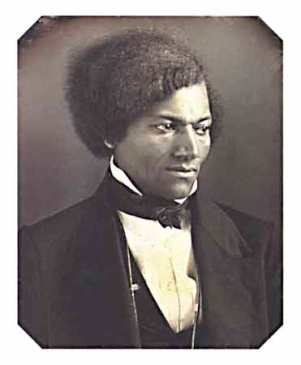

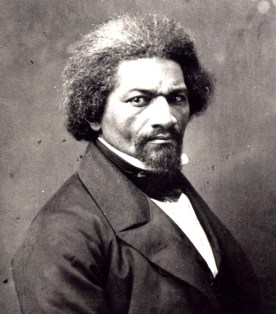

Frederick Douglass: From Slavery to Freedom

He was eight years old, sometime in the early 1800s, when he was sent as a slave to Baltimore to live with a ship carpenter named Mr. Hugh Auld. As Frederick Douglass wrote in his Narrative, “Going to live at Baltimore laid the foundation, and opened the gateway to all my subsequent prosperity.” But what happened in Baltimore that propelled Frederick so powerfully into “all” his future success? Well, soon after Frederick arrived at the Auld home, Mrs. Auld started teaching him the ABCs, after which he learned to spell small words. But, when Mr. Auld found out about this, he became angry and forbade Mrs. Auld from ever teaching him again, “…telling her, among other things that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe to teach a slave to read.” He went on to say, in front of young Frederick, “If you give a (n-word) an inch, he will take an ell. A (n-word) should know nothing but to obey his master–to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best (n-word) in the world…if you teach that (n-word) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.”

He was eight years old, sometime in the early 1800s, when he was sent as a slave to Baltimore to live with a ship carpenter named Mr. Hugh Auld. As Frederick Douglass wrote in his Narrative, “Going to live at Baltimore laid the foundation, and opened the gateway to all my subsequent prosperity.” But what happened in Baltimore that propelled Frederick so powerfully into “all” his future success? Well, soon after Frederick arrived at the Auld home, Mrs. Auld started teaching him the ABCs, after which he learned to spell small words. But, when Mr. Auld found out about this, he became angry and forbade Mrs. Auld from ever teaching him again, “…telling her, among other things that it was unlawful, as well as unsafe to teach a slave to read.” He went on to say, in front of young Frederick, “If you give a (n-word) an inch, he will take an ell. A (n-word) should know nothing but to obey his master–to do as he is told to do. Learning would spoil the best (n-word) in the world…if you teach that (n-word) how to read, there would be no keeping him. It would forever unfit him to be a slave. He would at once become unmanageable, and of no value to his master. As to himself, it could do him no good, but a great deal of harm. It would make him discontented and unhappy.”

These words changed Frederick forever. As he later wrote, “These words sank deep into my heart…I now understood what had been to me a most perplexing difficulty–to wit, the white man’s power to enslave the black man. It was a grand achievement, and I prized it highly. From that moment, I understood the pathway from slavery to freedom.” Frederick learned that education and slavery are incompatible. So, “Though conscious of the difficulty of learning without a teacher,” he said, “I set out with high hope, and a fixed purpose, at whatever cost of trouble, to learn how to read.”

But how did he learn to read with so much against him at such a young age (between eight and fifteen years old)? Well, as he later wrote, “The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge.”

But how did he learn to read with so much against him at such a young age (between eight and fifteen years old)? Well, as he later wrote, “The plan which I adopted, and the one by which I was most successful, was that of making friends of all the little white boys whom I met in the street. As many of these as I could, I converted into teachers. With their kindly aid, obtained at different times and in different places, I finally succeeded in learning to read. When I was sent of errands, I always took my book with me, and by going one part of my errand quickly, I found time to get a lesson before my return. I used also to carry bread with me, enough of which was always in the house, and to which I was always welcome; for I was much better off in this regard than many of the poor white children in our neighborhood. This bread I used to bestow upon the hungry little urchins, who, in return, would give me that more valuable bread of knowledge.”

Then, as Frederick stated, “I wished to learn how to write, as I might have occasion to write my own pass,” from slavery to freedom. And this is how he learned to write (and may I remind you that he did this between the age of eight and fifteen): “The idea as to how I might learn to write was suggested to me by being in Durgin and Bailey’s ship-yard, and frequently seeing the ship carpenters, after hewing, and getting a piece of timber ready for use, write on the timber the name of that part of the ship for which it was intended. When a piece of timber was intended for the larboard side, it would be marked thus–“L.” When a piece was for the starboard side, it would be marked thus–“S.” A piece for the larboard side forward, would be marked thus–“L. F.” When a piece was for starboard side forward, it would be marked thus–“S. F.” For larboard aft, it would be marked thus–“L. A.” For starboard aft, it would be marked thus–“S. A.” I soon learned the names of these letters, and for what they were intended when placed upon a piece of timber in the ship-yard. I immediately commenced copying them, and in a short time was able to make the four letters named. After that, when I met with any boy who I knew could write, I would tell him I could write as well as he. The next word would be, “I don’t believe you. Let me see you try it.” I would then make the letters which I had been so fortunate as to learn, and ask him to beat that. In this way I got a good many lessons in writing, which it is quite possible I should never have gotten in any other way. During this time, my copy-book was the board fence, brick wall, and pavement; my pen and ink was a lump of chalk. With these, I learned mainly how to write. I then commenced and continued copying the Italics in Webster’s Spelling Book, until I could make them all without looking on the book. By this time, my little Master Thomas had gone to school, and learned how to write, and had written over a number of copy-books. These had been brought home, and shown to some of our near neighbors, and then laid aside. My mistress used to go to class meeting at the Wilk Street meetinghouse every Monday afternoon, and leave me to take care of the house. When left thus, I used to spend the time in writing in the spaces left in Master Thomas’s copy-book, copying what he had written. I continued to do this until I could write a hand very similar to that of Master Thomas. Thus, after a long, tedious effort for years, I finally succeeded in learning how to write.”

Of course, true to Mr. Auld prediction, Frederick became “somewhat unmanageable” as a slave as he grew in knowledge and understanding, because, again, as he had learned, “education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” He also said, “I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason.” He understood this from personal experience. For example, when he was eventually transferred to a new plantation, his new master “succeeded in breaking me. I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!” By his own admission, Frederick was beaten into a beast by whips and rods. His zeal and desire was ripped from him. At times, the numerous whelps on his back from the physical abuse would be the size of a man’s finger. Yet, he did not quit. Instead, in a sense, he resurrected from the dead and then set his gaze anew upon his “pursuit of happiness.” And soon after that he began teaching other slaves to read and write, which set ablaze the fire of freedom in others. (At one time, he had over 40 students.)

Of course, true to Mr. Auld prediction, Frederick became “somewhat unmanageable” as a slave as he grew in knowledge and understanding, because, again, as he had learned, “education and slavery were incompatible with each other.” He also said, “I have found that, to make a contented slave, it is necessary to make a thoughtless one. It is necessary to darken his moral and mental vision, and, as far as possible, to annihilate the power of reason.” He understood this from personal experience. For example, when he was eventually transferred to a new plantation, his new master “succeeded in breaking me. I was broken in body, soul, and spirit. My natural elasticity was crushed, my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed, the cheerful spark that lingered about my eye died; the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!” By his own admission, Frederick was beaten into a beast by whips and rods. His zeal and desire was ripped from him. At times, the numerous whelps on his back from the physical abuse would be the size of a man’s finger. Yet, he did not quit. Instead, in a sense, he resurrected from the dead and then set his gaze anew upon his “pursuit of happiness.” And soon after that he began teaching other slaves to read and write, which set ablaze the fire of freedom in others. (At one time, he had over 40 students.)

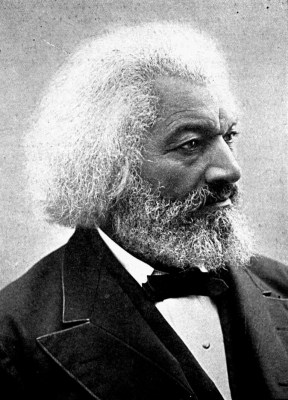

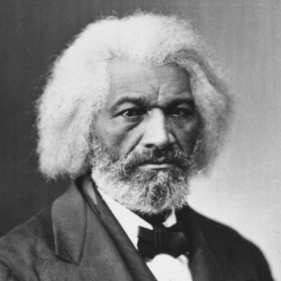

Ultimately, his passion for learning, which had liberated his mind, drove him to flee to the north for his freedom where he connected with the anti-slavery movement and soon became a renowned orator, writer, and editor.

In conclusion, as we consider Frederick Douglass’ life, as we ponder all he endured on his trek from slavery to freedom, what can we deduce? What lessons can we learn from his example? That learning is the way to freedom, that personal success is our personal responsibility, that when we “pick ourselves up by our boot-straps” we can create our own straps, and that self-determination and self-interest are powerful forces in the human spirit. When Frederick met hellish opposition, did he call the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), or the government for help? Did he allow institutional slavery and racism to keep him down? When he was beaten with rods and whips, did he relinquish himself to pity-parties or Affirmative Action? Education was Frederick’s ticket out of slavery because it gave him vision which led to incredible freedom and prosperity. He didn’t make excuses or blame others for his troubles. He didn’t wait for favorable circumstances. He didn’t hide behind victimhood or the race card, but used His God-given ingenuity, passion, and persistence to become the self-made man of merit he was born to be.

In conclusion, as we consider Frederick Douglass’ life, as we ponder all he endured on his trek from slavery to freedom, what can we deduce? What lessons can we learn from his example? That learning is the way to freedom, that personal success is our personal responsibility, that when we “pick ourselves up by our boot-straps” we can create our own straps, and that self-determination and self-interest are powerful forces in the human spirit. When Frederick met hellish opposition, did he call the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), or the government for help? Did he allow institutional slavery and racism to keep him down? When he was beaten with rods and whips, did he relinquish himself to pity-parties or Affirmative Action? Education was Frederick’s ticket out of slavery because it gave him vision which led to incredible freedom and prosperity. He didn’t make excuses or blame others for his troubles. He didn’t wait for favorable circumstances. He didn’t hide behind victimhood or the race card, but used His God-given ingenuity, passion, and persistence to become the self-made man of merit he was born to be.

Note: All quotes were taken from Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass by Frederick Douglass.

Written by Joel M. Killion